There was one big event in August: our Golden Wedding Anniversary on the 31st. We took a brief but thoroughly enjoyable holiday in Blakeney, North Norfolk the week before and organised a ‘get- together’ of family and friends, new and old, at the Depot in Lewes for the 1st September, during which we showed the film Guys and Dolls. One thing we didn’t plan for was the outbreak of a fire nearby (luckily after the screening). This meant we had to decamp from the Depot building itself to the lawned area in the grounds. Everything went very well in spite of this hiccup. Thanks to all for coming!

Repeated Hospital visits since January meant we weren’t able to participate in Art Wave this year We did, however, take in 2 Ringmer and 3 Lewes locations over a couple of days. As always, even on such a limited acquaintance, the work we saw was varied, skilful and innovative. We both feel we’ve got to catch up with ourselves and are sure to plan for Art wave next year. Unfortunately, Liz’s class in lino-cutting has ceased, although at least one workshop day has been planned, and she has now joined a drawing class at St Andrews in Lewes.

Amongst other things (books, films, choir, yoga) September saw us resuming our visits to Galleries. Here’s a brief mention of four shows we went to:

At the Towner, Eastbourne.

9th Sept. Edward Stott: Master of Colour and Atmosphere (16 May- 16 Sept). Stott (1855-1918) was a British artist born in Rochdale whose paintings of rural scenes in particular earned him a reputation as ‘the poet-painter of twilight’. After a late start he came under the influence in the 1880s of French naturalist and early impressionist painting. This gave his painting its admired rendering of light and atmosphere though at the cost, in our view, of the vitality and definition (in a painting such as ‘Feeding the Ducks’, 1885) which was more akin to the similarly ruralist work of the so-called Glasgow Boys (James Guthrie and George Henry amongst several others). After his success in Paris, Stott returned in 1885 to live and work in Amberley. West Sussex. Here, his continued commitment to depictions of everyday life and settings employing local people gave way to careful and sombre works on religious themes. I’m afraid we hurried past these last works.

Edward Stott, ‘Feeding the Ducks’,1885

Edward Stott, ‘Labourer’s Cottage – Suppertime’ 1893.

At Tate Britain

20th Sept. Aftermath, Art in the Wake of World War One (5th June -24th Sept).

We’d postponed visiting this exhibition but were in the event much impressed by the range of work displayed (from British, Belgian, German and French artists) and by its narrative organisation. Thus the display moves room by room from depictions of iconic aspects of the conflict itself (ruined landscapes, abandoned helmets), through grand public memorial ceremonies and generic sculptures, to bitter, satirical portraits of the maimed along with registrations of deep social and psychological disorder, and so to signs of broad change and a recovered or re-imagined world in the longer post-war period.

As the exhibition shows too these stages of reaction and response were marked by the adoption of different media, from paint, drawing and sculpture to photography and collage – whose cut-ups and juxtapositions told their own tale of jangled social and inner disturbance. Amongst many memorable works the Dadaist works by such as George Grosz and Otto Dix are perhaps the most striking in their innovative form and boldly politicised critiques of the war’s after-effects

George Grosz, ‘Grey Day’, 1921.

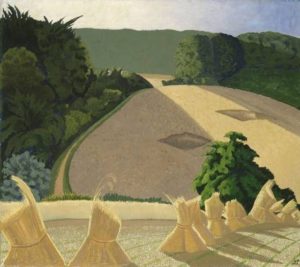

John Nash, ‘The Cornfield’, 1918.

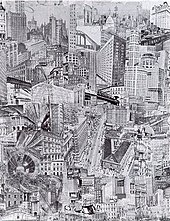

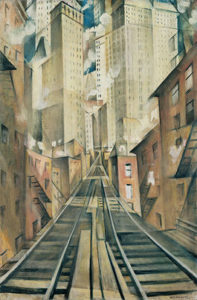

A key motif through all this to our eyes was machine technology; first of all in the automatic weapons, the tanks, and aircraft introduced in what was the first advanced industrial war and subsequently in the post-war advent of newly industrialised labour and the appearance of new workers’ organisations. While some (John Nash’s ‘The Cornfield’ here is an example) turned to the solace of the natural world, others (as here in Paul Citroen’s Metropolis) responded to new urban environments as a multi jig-sawed portrait of the modern world or as a beacon of new hope. New York City assumed a lasting symbolic role in this respect, but as the double title of C.R.W. Nevinson’s painting in the final room (‘New York – an Abstraction’ and ‘The Soul of a Soulless City’) showed, the new life of the new mass city could also appear empty.

Paul Citroen, ‘Metropolis’, 1923.

CRW. Nevinson, ‘The Soul of a Soulless City’ (New Y0rk –An Abstraction), 1920.

Keizer Frames Gallery, Lewes.

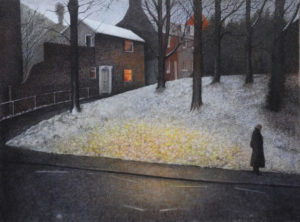

24th Sept. Peter Messer, ‘Tricks and Resolution (22nd Sept. – 7th Sept)

Simon Keizer curated this excellent small exhibition of new work by the Lewes based artist Peter Messer. Many will know Peter Messer’s extraordinarily meticulous paintings in egg tempera of familiar – but not so familiar, scenes in Lewes. We both found the works in this selection as engrossing as ever. Personally, Peter was pleased that while several somewhere secreted a comic or surrealist aside which upsets the otherwise normal and everyday, some paintings were ‘straight’ – which, in the context, was itself a little disarming. Messer had also included a written statement of his aims which in its unpretentious claims, less for himself than for the craft of painting, was itself winning and inspiring for anyone who wants to paint expertly.